Throughout history, musical intervals have been thought to express archetypal qualities and to create certain organizing effects by means of their numerical patterns. The perfect fourth “touches the heart, but at the same time awakens feelings of being controlled, making people uneasy. In the Medieval period, the perfect fourth was used in certain types of plainchant to reinforce the status quo, in which the Church had dominion over the hearts and souls of the populace.” The perfect fifth “is opening and stimulates power and movement. It can bring forth new life, creative ideas and rebirth. The fifth is also the functional fulcrum within an octave, in that it can facilitate movement either to the upper tonic note or a return to the fundamental… to express openness, joy, and healing.” The octave, an interval of two notes of identical pitches with the second note twice the frequency of the first, “is restful, meditative, calming, and grounding, and represents harmonious union.” Two notes in unison is the sound closest to “the primal cosmic union, and represents perfect serenity and peace.” 1 According to a Jungian analyst, "The pre-conscious aspect of natural numbers points to the idea of a numerical field in which individual numbers figure as energetic phenomena or rhythmical configurations… These numbers illustrated some of the most primitive and basic forms of the spirit. When we take into account the individual characteristics of natural numbers, we can actually demonstrate that they produce the same ordering effects in the physical and psychic realms; they therefore appear to constitute the most basic constants of nature expressing unitary psycho-physical reality."2

Without a doubt, certain intervals feel comfortable and pleasing and are perceived as unified rather than just a sum of their parts. To demonstrate this idea physiologically, University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA) lecturer and neurologist Mark Tramo performed an experiment in 1997 while at the Harvard Medical School. Wanting to answer the question, “why does sound make us feel so strongly?” he devised a method for recording electrical impulses directly from the human auditory apparatus. Pulsing and popping, the sound was discovered to have meter, similar to a metronome. “When the meter of electricity is regular and even and rhythmic, it’s interpreted as a sound we like, like a perfect fifth. When the meter is jagged or irregular, we hear it as a sound we generally don’t like, like a minor 2nd. It feels chaotic and makes a person feel uncomfortable. There is a relationship between the kind of electricity the sound produces and how we feel about the sound.”3

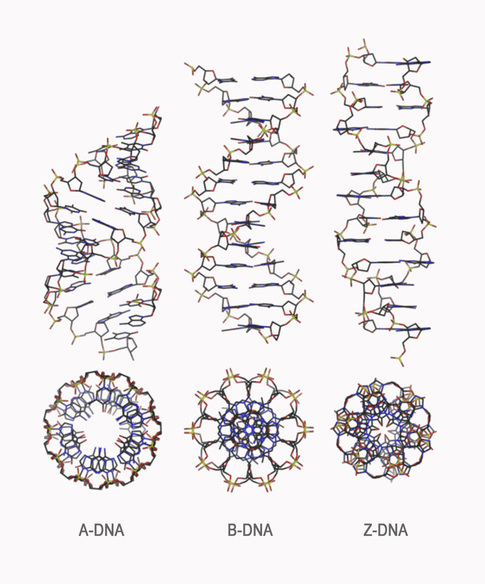

At the molecular level, a possible explanation regarding how we feel about and react to sound also could be linked to our DNA. When we examine the structure of DNA, again the Tetractys and the sound intervals it represents is implied. A strand of DNA (1) is a pair of molecules that intertwine to form the double helix (2), and although one geometry predominates, in nature the double helix can assume three slightly different geometries: A-DNA, B-DNA, and Z-DNA (3). Nucleotides, which are subunits of DNA, contain four base chemicals represented by the letters A,T,C,G (4). In the B-form of DNA, the one which is believed to predominate in our cells, the double helix makes a complete turn in just over ten nucleotide pairs. Like in the Tetractys, the pattern 1 + 2 + 3 + 4 = 10 emerges.

Content is available under Creative Commons License CC BY-SA 3.0

For more information about the geometries of DNA, see “Nucleic Acid Double Helix”:

http://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nucleic_acid_double_helix#

1 Wakefield, Mary Elizabeth. “Facial Soundscapes: Harmonic RenewalTM”.

2 von Franz, Marie-Louise. Number and Time: Reflections Leading Towards a Unification of Psychology and Physics. Rider & Company, London, 1974, page 19 and 303.

3 Radio Lab. http://www.radiolab.org/2007/sep/24/

RSS Feed

RSS Feed