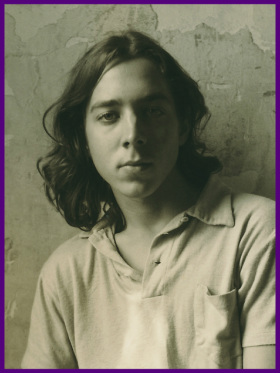

Stephen, age 20

Stephen, age 20 of four children from a middle class Philadelphia suburb. Although all of the children are accomplished in their own ways, Stephen was the “golden child”, the son who had everything:

a brilliant and inquisitive mind, a great sense of humor, literary and musical talent, and striking good looks. His huge, intelligent blue-green eyes were always observing, always analyzing, always questioning.

Stephen’s passions were Native American culture and African drumming, and over twenty years ago he relocated to New Mexico. He taught cultural anthropology at Santa Fe Community College and often organized drums circles at his Española, New Mexico, hacienda, held in the shade of a hundred-year-old cottonwood tree and accompanied by the bleating of his small herd of goats. Stephen organized a dedicated community of enthusiastic drummers, exposing people to music and to cultures they might not otherwise have encountered.

He wrote articles on music and anthropology that appeared in magazines and alternative newspapers, and his magnum opus is a book called Apocalyptic Grace, an exploration of five distinct eras of cultural (socio-economic, psychological, and spiritual) evolution.

Unfortunately, during the past ten years Stephen’s health was often compromised. In early 2014 he was diagnosed with advanced liver cancer.

His employer did not offer health insurance so Stephen sought treatment in Mexico at a facility across the border from San Diego. Stephen’s network of over two thousand friends and his Community College students raised several thousands of dollars to help pay for his treatments in Mexico, but it was already too late. By summer, the cancer had advanced to stage four and Stephen was tortured by intractable pain. Friends and acquaintances appeared at his door

to drum for him, to bring food, and most important, to express their gratitude for the learning, love, and joy Stephen brought to their lives. During the last month of his life, Stephen’s former partner of six years, Treaca, arrived from Arizona to take care of him full-time.

Not wanting to dull his mind with strong pain killers, he turned to a variety of integrative (“complementary”) healing modalities, and tuning fork therapy was one of them. I gave him his first treatment on June 22, 2014, and continued to see him until a few days before his untimely death at age 58.

Excerpted from my diary, the following are comments Stephen made about his treatments:

6/29/14: “It neutralizes the pain.”

7/6/14: “I feel better in my body.”

7/7/14: As I was applying high frequencies above his body, he said, “this is so beautiful.”

7/9/14: When I asked how long the treatments abated his pain, he replied, “about a day and a half.”

7/13/14: When I arrived to treat Stephen, he said, “Laurie to the rescue!” During his treatment he wanted to listen to loud gospel-funk music and I thought, "why not?" When you provide care to someone who only has a few days to live, you do what they ask. At a crescendo in the music, while lying

on his side, Stephen thrust his right arm into the air as if “testifying” and managed to wiggle his body and head a little to the beat of the music. This is the power of music: to inspire someone so overwhelmed with pain to forget for a few moments and to move. I stayed the night giving him mini-treatments, applying sound to the body’s major pain points that I could access (he was comfortable lying on his left side only). I applied the forks to Stephen’s head for sedation.

Those of us who visited Stephen regularly saw him cycle through emotions ranging from acceptance and calm to terror and disbelief. Tonight Stephen said, “I’m really going to miss this”, meaning the human interaction and love

he had experienced over the past few months. Clearly he was not ready to let go of life and move on, even though his body was literally reduced to skin and bones and he could barely move he was so weak. But he was seeing angels, so he was close. One of his hospice nurses said that near the end all of her clients talk about the presence of angels, even if they are atheists.

Even though he was a well-respected professor and something of a public persona, Stephen confessed that he was a lonely person. To his mind, he could never create the depth of connection with someone else that he longed for and wanted so badly. The last time we talked, on July 14th, he expressed a great deal of shame about what he perceived as a character flaw. He understood that he had created impediments to the thing he wanted most, reaching the end of his life with an important life goal unrealized. It was difficult to find a way to comfort and assure him that he was loved and accepted by many people and that he had touched other’s lives in a deeply profound way. Stephen imparted an important lesson: to let those you have touched touch you in return. Let down the barriers if you possibly can.

During his last moments on Earth, Stephen asked to be placed beneath the canopy of the cottonwood tree where so many drumming circles had taken place. Two members of his men’s group carried him outside and lay him within a medicine wheel Stephen had created, in a thick patch of chipilín* nurtured by the monsoon rains. They held his hands while he gazed up into the sky, the cottonwood leaves sounding like soft applause in the breeze, when Stephen took his final breath late in the afternoon on July 18th.

*an edible Mexican green

RSS Feed

RSS Feed